Chapter 4: Money Talks: Payments in Value-Based Care

This post is part of a series of blog posts aimed at unpacking value based payment for primary care practices looking to make the transition to value based care. Click here to read more about how Elation supports the transition to value based payment.

By: Dr. Sara Pastoor & Kristen Caldarella

In our previous chapters, we learned that making the transition from FFS to VBP requires a practice to 1) embrace a new incentive structure and 2) make considerable operational and process changes within their practice. Even though VBP arrangements aren’t free of challenges, these are often adjustments that practices are willing to work through in the greater interest of delivering better care.

Let’s say there is a physician who is excited about VBP and wants to make the leap into this new payment paradigm. Can they simply wake up one morning and flip a switch, changing their whole practice from a FFS model to a VBP model?

Not quite!

Practices typically migrate gradually along the value-based continuum which can take years to complete, and independent practices rarely break free of at least partial FFS payments.

Unlike FFS which is carried out in a uniform way across the U.S., there isn’t a single, unified VBP program that covers all patients at once. In fact, the average primary care practice contracts with 25 payers. It’s up to each payer to decide whether to offer VBP payment options and how each VBP contract is designed. As a result, a provider’s transition to VBP is often done in a patchwork way - payer by payer - with each payer requiring a different set of performance measures and having different definitions of success.

Thus we see that there is tremendous diversity in value based payment arrangements, both between practices and within a single practice. This diversity drives complexity and increases administrative burden for practices already struggling to survive in FFS. The conundrum of remaining partially in FFS while also trying to evolve care delivery to achieve success in value-based arrangements that lack uniformity across payers and patient populations has been described as having “a foot in two canoes”, and is the primary factor slowing VBP adoption across the industry.

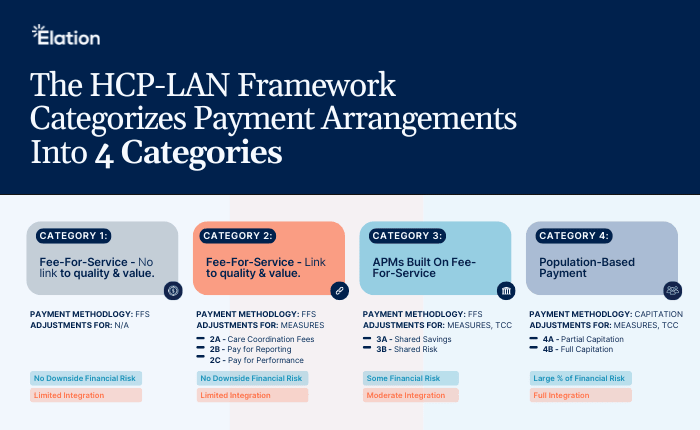

To help make sense of the diversity in VBP arrangements, the Healthcare Payment Learning and Action Network (HCP-LAN), created a framework to organize the various arrangements into four categories. This framework is used to identify the type of incentives included in the model and their relationship to quality and value.

Key Takeaways of the HCP-LAN Framework:

-

- The increase in risk and value - As we move from left to right, each successive category ties more of the practice’s total payment to their ability to deliver value. Value is quantified at first by using performance measures and later by the practice’s influence on total cost of care (in addition to performance measures). As we move to the right, the practice takes on more financial risk in exchange for the opportunity to gain a larger share of cost savings. This means that if costs increase for a population, the practice has to pay a portion of the additional cost back to the payer.

-

The gradual removal of FFS- The majority of VBP models are still built on top of a FFS foundation, and FFS doesn’t make a full exit until we reach specific models within Category 4. However, as we move along the continuum, transactional FFS payments are gradually replaced by prospective, population-based payments, and it becomes more difficult for a practice to succeed financially by merely increasing the volume of services. This is intentional so that practices become increasingly financially invested in care delivery that maximizes quality while containing cost.

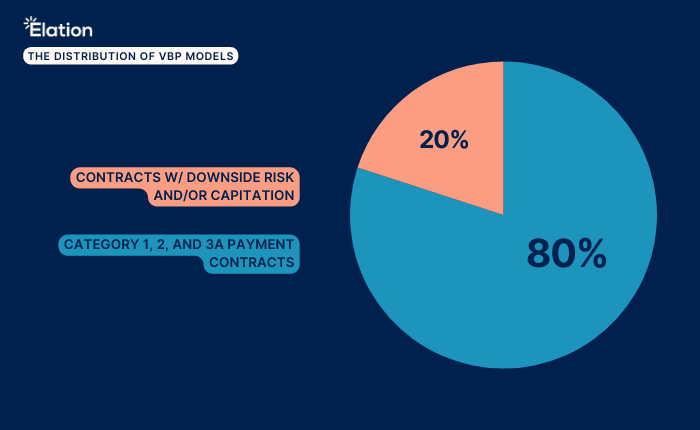

The distribution of various VBP models

If the shared risk and capitation of VBP Categories 3B and 4 allow us to finally step away from FFS mechanisms, why don’t we see more of these contracts?

From a practice’s perspective, becoming proficient and ultimately successful in VBP contracts takes years of investment in care delivery redesign and operational iteration. It requires financial resources, technical resources, human resources, and a complete overhaul of workflows. Unfortunately, legacy billing systems and clinical technology are not designed to support success in these payment models. Consequently, practices who are new to VBP typically take a conservative approach and pursue contracts with no financial risk (i.e. Categories 2 and 3A) so that they can ensure adequate revenue through traditional FFS mechanisms while testing out and evolving their competencies in less advanced value-based arrangements. As these practices build expertise (and new revenue streams) in VBP, the hope is that they will be more likely to consider contracts further along the continuum.

Even though VBP holds a lot of promise, there are numerous barriers to adoption. The added work, the learning curve, the diversity of requirements, the inadequate technology, and the considerable degree of change management required not only stymie initial adoption, but also create obstacles that prevent migration into higher-category arrangements. The good news is that the industry is responding with a variety of solutions to help primary care through this turbulence and usher them into a new payment era in healthcare.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explored how VBP contracts are characterized using the HCP-LAN framework and the incremental ways in which value-based requirements are incorporated into these payment models - particularly how performance measures are prevalent across all categories and how total cost of care becomes a key feature in more advanced models. VBP contracts offered by payers can fall anywhere along the HCP-LAN continuum, and practices enter into the contracts that best fit their capacity for change and tolerance for risk.

We also explored the barriers to adoption, the inherent challenges of having “a foot in two canoes”, and the complexities introduced by diversity across payers. As such, we see that VBP holds both promise and peril, and there is work to be done across the industry to better support the efforts of primary care to take the leap into VBP.

In the following and final chapter, we will focus on how providers enter value-based payment arrangements.